تاريخ النشر:25.11.2020 | 17:00 GMT |

آخر تحديث:25.11.2020 | 17:16 GMT | الرياضة

Reuters Juan Mabromata

رئيس الأرجنتين، ألبرتو فرنانديز

أعلن رئيس الأرجنتين، ألبرتو فرنانديز، اليوم الأربعاء، الحداد ثلاثة أيام على رحيل أسطورة كورة القدم الأرجنتيني، دييغو مارادونا.

وفاة أسطورة كرة القدم الأرجنتيني دييغو مارادونا عن عمر ناهز 60 عاما

وجاء في بيان أصدره المكتب الإعلامي للرئاسة الأرجنتينية: “بمناسبة رحيل دييغو أرماندو مارادونا سيعلن رئيس البلاد الحداد ثلاثة أيام اعتبارا من اليوم”.

وقدمت نائبة رئيس الجمهورية كريستينا فرنانديز دي كيرشنر التي كانت صديقة لمارادونا تعازيها لعائلته وذويه وكتبت على “تويتر”: “وداعا يا مارادونا، نحبك حبا جما”.

وتوفي مارادونا اليوم عن 60 عاما.

المصدر: نوفوستي

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

Diego Maradona

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

“Maradona” redirects here. For the 2019 documentary film, see Diego Maradona (film). For other uses, see Maradona (disambiguation).

In this Spanish name, the first or paternal family name is Maradona and the second or maternal family name is Franco.

Diego Maradona

Maradona 1986 vs italy.jpg

Maradona playing for Argentina against Italy at the 1986 World Cup

Personal information

Full name Diego Armando Maradona Franco[1]

Date of birth 30 October 1960

Place of birth Lanús, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Date of death 25 November 2020 (aged 60)

Place of death Tigre, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Height 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in)[2]

Playing position(s) Attacking midfielder

Second striker[3][4][5][6]

Senior career*

Years Team Apps (Gls)

1976–1981 Argentinos Juniors 167 (116)

1981–1982 Boca Juniors 40 (28)

1982–1984 Barcelona 36 (22)

1984–1991 Napoli 188 (81)

1992–1993 Sevilla 26 (5)

1993–1994 Newell’s Old Boys 5 (0)

1995–1997 Boca Juniors 30 (7)

Total 491 (259)

National team

1977–1979 Argentina U20 15 (8)

1977–1994 Argentina 91 (34)

Teams managed

1994 Textil Mandiyú

1995 Racing Club

2008–2010 Argentina

2011–2012 Al-Wasl

2013–2017 Deportivo Riestra (assistant)

2017–2018 Fujairah

2018–2019 Dorados de Sinaloa

2019–2020 Gimnasia de La Plata

Honours[show]

Senior club appearances and goals counted for the domestic league only

Diego Armando Maradona Franco (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈdjeɣo maɾaˈðona] 30 October 1960 – 25 November 2020) was an Argentine professional football player and manager. Widely regarded as one of the greatest players of all time, he was one of the two joint winners of the FIFA Player of the 20th Century award.[7][8] Maradona’s vision, passing, ball control and dribbling skills were combined with his small stature (1.65 metres (5 ft 5 in)), which gave him a low centre of gravity allowing him to manoeuvre better than most other football players; he would often dribble past multiple opposing players on a run. His presence and leadership on the field had a great effect on his team’s general performance, while he would often be singled out by the opposition. In addition to his creative abilities, he also possessed an eye for goal and was known to be a free-kick specialist. A precocious talent, Maradona was given the nickname “El Pibe de Oro” (“The Golden Boy”), a name that stuck with him throughout his career.[9]

An advanced playmaker who operated in the classic number 10 position, Maradona was the first player in football history to set the world record transfer fee twice, first when he transferred to Barcelona for a then-world record £5 million, and second, when he transferred to Napoli for another record fee £6.9 million.[10] He played for Argentinos Juniors, Boca Juniors, Barcelona, Napoli, Sevilla and Newell’s Old Boys during his club career, and is most famous for his time at Napoli and Barcelona where he won numerous accolades.

In his international career with Argentina, he earned 91 caps and scored 34 goals. Maradona played in four FIFA World Cups, including the 1986 World Cup in Mexico where he captained Argentina and led them to victory over West Germany in the final, and won the Golden Ball as the tournament’s best player. In the 1986 World Cup quarter final, he scored both goals in a 2–1 victory over England that entered football history for two different reasons. The first goal was an unpenalized handling foul known as the “Hand of God”, while the second goal followed a 60 m (66 yd) dribble past five England players, voted “Goal of the Century” by FIFA.com voters in 2002.[11]

Maradona became the coach of Argentina’s national football team in November 2008. He was in charge of the team at the 2010 World Cup in South Africa before leaving at the end of the tournament. He then coached Dubai-based club Al Wasl in the UAE Pro-League for the 2011–12 season. In 2017, Maradona became the coach of Fujairah before leaving at the end of the season.[12] In May 2018, Maradona was announced as the new chairman of Belarusian club Dynamo Brest.[13] He arrived in Brest and was presented by the club to start his duties in July.[14] From September 2018 to June 2019, Maradona was coach of Mexican club Dorados.[15] He was the coach of Argentine Primera División club Gimnasia de La Plata from 2019 until his death.[16]

Early years

Maradona playing at the Torneos Evita in 1973 (a national sporting event in Argentina) with the “Cebollitas”

“When Diego came to Argentinos Juniors for trials, I was really struck by his talent and couldn’t believe he was only eight years old. In fact, we asked him for his ID card so we could check it, but he told us he didn’t have it on him. We were sure he was having us on because, although he had the physique of a child, he played like an adult. When we discovered he’d been telling us the truth, we decided to devote ourselves purely to him.”

—Francisco Cornejo, youth coach who discovered Maradona[17]

Diego Armando Maradona was born on 30 October 1960, at the Policlínico (Polyclinic) Evita Hospital in Lanús, Buenos Aires Province, to a poor family that had moved from Corrientes Province; he was raised in Villa Fiorito, a shantytown on the southern outskirts of Buenos Aires, Argentina.[18] He was the first son after four daughters. He has two younger brothers, Hugo (el Turco) and Raúl (Lalo), both of whom were also professional football players. His parents were Diego Maradona “Chitoro” (d. 2015) and Dalma Salvadora Franco ‘Doña Tota’ (1930–2011). They were both born and brought up in the town of Esquina in the north-east province of Corrientes Province, living only two hundred metres from each other on the banks of the Corriente River. In 1950, they left Esquina and settled in Buenos Aires. At age eight, Maradona was spotted by a talent scout while he was playing in his neighbourhood club Estrella Roja. He became a staple of Los Cebollitas (The Little Onions), the junior team of Buenos Aires’s Argentinos Juniors. As a 12-year-old ball boy, he amused spectators by showing his wizardry with the ball during the halftime intermissions of first division games.[19] He named Brazilian playmaker Rivelino and Manchester United winger George Best among his inspirations growing up.[20][21]

Club career

Argentinos Juniors and Boca Juniors

Maradona’s most famous nutmeg, the day he debuted in Primera División, 20 October 1976

On 20 October 1976, Maradona made his professional debut for Argentinos Juniors, 10 days before his 16th birthday,[22] vs. Talleres de Córdoba. He entered to the pitch wearing the number 16 jersey, and became the youngest player in the history of Argentine Primera División. Few minutes after debuting, Maradona kicked the ball through Juan Domingo Cabrera’s legs, making a nutmeg that would become legendary.[23] After the game, Maradona said, “That day I felt I had held the sky in my hands.”[24] Thirty years later, Cabrera remembered Maradona’s debut: “I was on the right side of the field and went to press him, but he didn’t give me a chance. He made the nutmeg and when I turned around, he was far away from me”.[25] Maradona scored his first goal in the Primera División against Marplatense team San Lorenzo on 14 November 1976, two weeks after turning 16.[26]

Maradona being held aloft by fans of Boca Juniors after winning the 1981 Metropolitano championship

Maradona spent five years at Argentinos Juniors, from 1976 to 1981, scoring 115 goals in 167 appearances before his US$ 4 million transfer to Boca Juniors.[27] Maradona received offers to join other clubs, including River Plate who offered to make him the club’s best paid player.[28] Nevertheless, Maradona expressed his will to be transferred to Boca Juniors, the team he always wanted to play for.[29]

Maradona signed a contract with Boca Juniors on 20 February 1981. He made his debut two days later against Talleres de Córdoba, scoring twice in the club’s 4–1 win. On 10 April, Maradona played his first Superclásico against River Plate at La Bombonera stadium. Boca defeated River 3–0 with Maradona scoring a goal after dribbling past Alberto Tarantini and Fillol.[30] Despite the distrustful relationship between Maradona and Boca Juniors manager, Silvio Marzolini,[31] Boca had a successful season, winning the league title after securing a point against Racing Club.[32] That would be the only title won by Maradona in the Argentine domestic league.[33]

Barcelona

“He had complete mastery of the ball. When Maradona ran with the ball or dribbled through the defence, he seemed to have the ball tied to his boots. I remember our early training sessions with him: the rest of the team were so amazed that they just stood and watched him. We all thought ourselves privileged to be witnesses of his genius.”

—Barcelona teammate Lobo Carrasco[34]

After the 1982 World Cup, in June, Maradona was transferred to Barcelona in Spain for a then world record fee of £5 million ($7.6 million).[35] In 1983, under coach César Luis Menotti, Barcelona and Maradona won the Copa del Rey (Spain’s annual national cup competition), beating Real Madrid, and the Spanish Super Cup, beating Athletic Bilbao. On 26 June 1983, Barcelona defeated Real Madrid on the road in one of the world’s biggest club games, El Clásico, a match where Maradona scored and became the first Barcelona player to be applauded by archrival Real Madrid fans.[36] Maradona dribbled past Madrid goalkeeper Agustín, and as he approached the empty goal, he stopped just as Madrid defender Juan José came sliding in a desperate attempt to block the shot and ended up crashing into the post, before Maradona slotted the ball into the net.[37] The manner of the goal led to many inside the stadium start applauding; only Ronaldinho (in November 2005) and Andrés Iniesta (in November 2015) have since been granted such an ovation as Barcelona players from Madrid fans at the Santiago Bernabéu.[36][38]

The moment when Atlético de Bilbao player Andoni Goikoetxea injures Diego Maradona on 24 September 1983

Due to illness and injury as well as controversial incidents on the field, Maradona had a difficult tenure in Barcelona.[39] First a bout of hepatitis, then a broken ankle in a La Liga game at the Camp Nou in September 1983 caused by an ill-timed tackle by Athletic Bilbao’s Andoni Goikoetxea, threatened to jeopardize Maradona’s career, but with treatment and therapy, it was possible for him to return to the pitch after a three-month recovery period.[22]

Maradona with his fellow countryman Mario Kempes before a Barcelona match against Valencia

The end of the 1983–84 season included a violent and chaotic fight Maradona was directly involved in at the 1984 Copa del Rey final at the Santiago Bernabéu in Madrid against Athletic Bilbao.[40] After receiving another rough tackle by Goikoetxea which wounded his leg, being taunted with xenophobic, racist insults related to his father’s Native American ancestry throughout the match by Bilbao fans, and being provoked by Bilbao’s Miguel Sola at full time as Barcelona lost 1–0, Maradona snapped.[40] He aggressively got up, stood inches from Sola’s face and the two exchanged words. This started a chain reaction of emotional reactions from both teams. Using expletives, Sola mimicked a gesture from the crowd towards Maradona by using a xenophobic term.[41] Maradona then headbutted Sola, elbowed another Bilbao player in the face and kneed another player in the head, knocking him out cold.[40] The Bilbao squad surrounded Maradona to exact some retribution with Goikoetxea connecting with a high kick to his chest, before the rest of the Barcelona squad joined in to help Maradona. From this point, Barcelona and Bilbao players brawled on the field with Maradona in the centre of the action, kicking and punching anyone in a Bilbao shirt.[40]

The mass brawl was played out in front of the Spanish King Juan Carlos and an audience of 100,000 fans inside the stadium, and more than half of Spain watching on television.[42] After fans began throwing solid objects on the field at the players, coaches and even photographers, sixty people were injured, with the incident effectively sealing Maradona’s transfer out of the club in what was his last game in a Barcelona shirt.[41] One Barcelona executive stated, “When I saw those scenes of Maradona fighting and the chaos that followed I realized we couldn’t go any further with him.”[42] Maradona got into frequent disputes with FC Barcelona executives, particularly club president Josep Lluís Núñez, culminating with a demand to be transferred out of Camp Nou in 1984. During his two injury-hit seasons at Barcelona, Maradona scored 38 goals in 58 games.[43] Maradona transferred to Napoli in Italy’s Serie A for another world record fee, £6.9 million ($10.48M).[10]

Napoli

Maradona saluting the crowd at the Stadio San Paolo in Naples during his presentation on 5 July 1984

Maradona arrived in Naples and was presented to the world media as a Napoli player on 5 July 1984, where he was welcomed by 75,000 fans at his presentation at the Stadio San Paolo.[44] Sports writer David Goldblatt commented, “They [the fans] were convinced that the saviour had arrived.”[45] A local newspaper stated that despite the lack of a “mayor, houses, schools, buses, employment and sanitation, none of this matters because we have Maradona”.[45] Prior to Maradona’s arrival, Italian football was dominated by teams from the north and centre of the country, such as A.C. Milan, Juventus, Inter Milan and Roma, and no team in the south of the Italian Peninsula had ever won a league title.[45][46]

At Napoli, Maradona reached the peak of his professional career: he soon inherited the captain’s armband from Napoli veteran defender Giuseppe Bruscolotti[47] and quickly became an adored star among the club’s fans; in his time there he elevated the team to the most successful era in its history.[45] Maradona played for Napoli at a period when north–south tensions in Italy were at a peak due to a variety of issues, notably the economic differences between the two.[45] Led by Maradona, Napoli won their first ever Serie A Italian Championship in 1986–87.[45] Goldblatt wrote, “The celebrations were tumultuous. A rolling series of impromptu street parties and festivities broke out contagiously across the city in a round-the-clock carnival which ran for over a week. The world was turned upside down. The Neapolitans held mock funerals for Juventus and Milan, burning their coffins, their death notices announcing ‘May 1987, the other Italy has been defeated. A new empire is born.'”[45] Murals of Maradona were painted on the city’s ancient buildings, and newborn children were named in his honour.[45] The following season, the team’s prolific attacking trio, formed by Maradona, Bruno Giordano and Careca, was later dubbed the “Ma-Gi-Ca” (magical) front-line.[48]

Napoli would win their second league title in 1989–90, and finish runners up in the league twice, in 1987–88 and 1988–89.[45] Other honours during the Maradona era at Napoli included the Coppa Italia in 1987, (as well as a second-place finish in the Coppa Italia in 1989), the UEFA Cup in 1989 and the Italian Supercup in 1990.[45] During the 1989 UEFA Cup Final against Stuttgart, Maradona scored from a penalty in a 2–1 home victory in the first leg, later assisting Careca’s match–winning goal,[49][50] while in the second leg on 17 May – a 3–3 away draw –, he assisted Ciro Ferrara’s goal with a header.[51][52] Despite primarily playing in a creative role as an attacking midfielder, Maradona was the top scorer in Serie A in 1987–88, with 15 goals, and was the all-time leading goalscorer for Napoli, with 115 goals,[53] until his record was broken by Marek Hamšík in 2017.[33][54][55] When asked who was the toughest player he ever faced, A.C. Milan central defender Franco Baresi stated, that it was Maradona, a view shared by his Milan teammate Paolo Maldini, who viewed Maradona and Ronaldo as the best players he ever faced, stating in 2008, “The best ever I played against was Maradona.”[56][57]

While Maradona was successful on the field during his time in Italy, his personal problems increased. His cocaine use continued, and he received US$70,000 in fines from his club for missing games and practices, ostensibly because of “stress”.[58] He faced a scandal there regarding an illegitimate son, and he was also the object of some suspicion over an alleged friendship with the Camorra.[59][60][61][62] Later on, in honour of Maradona and his achievements during his career at Napoli, the number 10 jersey of Napoli was officially retired.[63]

Sevilla, Newell’s Old Boys and Boca Juniors

After serving a 15-month ban for failing a drug test for cocaine, Maradona left Napoli in disgrace in 1992. Despite interest from Real Madrid and Marseille, he signed for Sevilla, where he stayed for one year.[64] In 1993, he played for Newell’s Old Boys and in 1995 returned to Boca Juniors for a two-year stint.[22] Maradona also appeared for Tottenham Hotspur in a testimonial match for Osvaldo Ardiles against Internazionale, shortly before the 1986 World Cup.[65] Maradona was himself given a testimonial match in November 2001, played between an all-star World XI and the Argentina national team.[66]

International career

Maradona on the ball against the Soviet Union at the 1979 FIFA World Youth Championship final

During his time with the Argentina national team, Maradona scored 34 goals in 91 appearances. He made his full international debut at age 16, against Hungary, on 27 February 1977. Maradona was left off the Argentine squad for the 1978 World Cup on home soil by coach César Luis Menotti who felt he was too young at age 17.[67] At age 18, Maradona played the 1979 FIFA World Youth Championship in Japan and emerged as the star of the tournament, shining in Argentina’s 3–1 final win over the Soviet Union, scoring a total of six goals in six appearances in the tournament.[68] On 2 June 1979, Maradona scored his first senior international goal in a 3–1 win against Scotland at Hampden Park.[69] He went on to play for Argentina in two 1979 Copa América ties during August 1979, a 2–1 loss against Brazil and a 3–0 win over Bolivia in which he scored his side’s third goal.[70]

Speaking thirty years later on the impact of Maradona’s performances in 1979, FIFA President Sepp Blatter stated, “Everyone has an opinion on Diego Armando Maradona, and that’s been the case since his playing days. My most vivid recollection is of this incredibly gifted kid at the second FIFA U-20 World Cup in Japan in 1979. He left everyone open-mouthed every time he got on the ball.”[71] Maradona and his compatriot Lionel Messi are the only players to win the Golden Ball at both the FIFA U-20 World Cup and FIFA World Cup. Maradona did so in 1979 and 1986, which Messi emulated in 2005 and 2014.[72]

1982 World Cup

Maradona played his first World Cup tournament in 1982 in his new country of residence, Spain. Argentina played Belgium in the opening game of the 1982 Cup at the Camp Nou in Barcelona. The Catalan crowd was eager to see their new world-record signing Maradona in action, but he did not perform to expectations,[73] as Argentina, the defending champions, lost 1–0. Although the team convincingly beat both Hungary and El Salvador in Alicante to progress to the second round, there were internal tensions within the team, with the younger, less experienced players at odds with the older, more experienced players. In a team that also included such players as Mario Kempes, Osvaldo Ardiles, Ramón Díaz, Daniel Bertoni, Alberto Tarantini, Ubaldo Fillol and Daniel Passarella, the Argentine side was defeated in the second round by Brazil and by eventual winners Italy. The Italian match is renowned for Maradona being aggressively man-marked by Claudio Gentile, as Italy beat Argentina at the Sarrià Stadium in Barcelona, 2–1.[74]

Maradona played in all five matches without being substituted, scoring twice against Hungary. He was fouled repeatedly in all five games and particularly in the last one against Brazil at the Sarrià, a game that was blighted by poor officiating and violent fouls. With Argentina already down 3–0 to Brazil, Maradona’s temper eventually got the better of him and he was sent off with five minutes remaining for a serious retaliatory foul against Batista.[75]

1986 World Cup

Maradona holding the 1986 World Cup trophy

Maradona captained the Argentine national team to victory in the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, winning the final in Mexico City against West Germany.[76] Throughout the tournament, Maradona asserted his dominance and was the most dynamic player of the tournament. He played every minute of every Argentina game, scoring five goals and making five assists, three of those in the opening match against South Korea at the Olimpico Universitario Stadium in Mexico City. His first goal of the tournament came against Italy in the second group game in Puebla.[77] Argentina eliminated Uruguay in the first knockout round in Puebla, setting up a match against England at the Azteca Stadium, also in Mexico City. After scoring two contrasting goals in the 2–1 quarter-final win against England, his legend was cemented. The majesty of his second goal and the notoriety of his first led to the French newspaper L’Equipe describing Maradona as “half-angel, half-devil”.[78] This match was played with the background of the Falklands War between Argentina and the United Kingdom. Replays showed that the first goal was scored by striking the ball with his hand. Maradona was coyly evasive, describing it as “a little with the head of Maradona and a little with the hand of God”.[76] It became known as the “Hand of God”. Ultimately, on 22 August 2005, Maradona acknowledged on his television show that he had hit the ball with his hand purposely, and no contact with his head was made, and that he immediately knew the goal was illegitimate. This became known as an international fiasco in World Cup history. The goal stood, much to the wrath of the English players.[79]

“Maradona, turns like a little eel and comes away from trouble, little squat man… comes inside Butcher and leaves him for dead, outside Fenwick and leaves him for dead, and puts the ball away… and that is why Maradona is the greatest player in the world.”

—Bryon Butler’s BBC Radio commentary on Maradona’s second goal against England[80]

Maradona’s second goal, just four minutes after the hotly disputed hand-goal, was later voted by FIFA as the greatest goal in the history of the World Cup. He received the ball in his own half, swivelled around and with 11 touches ran more than half the length of the field, dribbling past five English outfield players (Peter Beardsley, Steve Hodge, Peter Reid, Terry Butcher and Terry Fenwick) before he left goalkeeper Peter Shilton on his backside with a feint, and slotted the ball into the net.[81] This goal was voted “Goal of the Century” in a 2002 online poll conducted by FIFA.[11] A 2002 Channel 4 poll in the UK saw his performance ranked number 6 in the list of the 100 Greatest Sporting Moments.[82]

Maradona right before scoring the “Goal of the Century” against England in Mexico 1986

Maradona followed this with two more goals in a semi-final match against Belgium at the Azteca, including another virtuoso dribbling display for the second goal. In the final match, West Germany attempted to contain him by double-marking, but he nevertheless found the space past the West German player Lothar Matthäus to give the final pass to Jorge Burruchaga for the winning goal. Argentina beat West Germany 3–2 in front of 115,000 fans at the Azteca with Maradona lifting the World Cup as captain.[78][83]

During the course of the tournament, Maradona attempted or created more than half of Argentina’s shots, attempted a tournament best 90 dribbles – some three times more than any other player – and was fouled a record 53 times, winning his team twice as many free kicks as any player.[84][85] Maradona scored or assisted 10 of Argentina’s 14 goals (71%), including the assist for the winning goal in the final, ensuring that he would be remembered as one of the greatest names in football history.[85][86] By the end of the World Cup, Maradona went on to win the Golden Ball as the best player of the tournament by unanimous vote and was widely regarded to have won the World Cup virtually single-handedly, something that he later stated he did not entirely agree with.[85][87][88][89] Zinedine Zidane, watching the 1986 World Cup as a 14-year-old, stated Maradona “was on another level”.[90] In a tribute to him, Azteca Stadium authorities built a statue of him scoring the “Goal of the Century” and placed it at the entrance of the stadium.[91]

Regarding Maradona’s performance at the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, in 2014, Roger Bennett of ESPN FC described it as “the most virtuoso performance a World Cup has ever witnessed,”[92] while Kevin Baxter of the Los Angeles Times called it “one of the greatest individual performances in tournament history,”[93] with Steven Goff of The Washington Post instead dubbing his performance as “one of the finest in tournament annals.”[94] In 2002, Russell Thomas of The Guardian described Maradona’s second goal against England in the 1986 World Cup quarter-finals as “arguably the greatest individual goal ever.”[95] In a 2009 article for CBC Sports, John Molinaro described the goal as “the greatest ever scored in the tournament – and, maybe, in soccer.”[96] In a 2018 article for Sportsnet, he added: “No other player, not even Pel[é] in 1958 nor Paolo Rossi in 1982, had dominated a single competition the way Maradona did in Mexico.” He also went on to say of Maradona’s performance: “The brilliant Argentine artist single-handedly delivered his country its second World Cup.” Regarding his two memorable goals against England in the quarter-finals, he commented: “Yes, it was Maradona’s hand, and not God’s, that was responsible for the first goal against England. But while the ‘Hand of God’ goal remains one of the most contentious moments in World Cup history, there can be no disputing that his second goal against England ranks as the greatest ever scored in the tournament. It transcended mere sports – his goal was pure art.”[97]

1990 World Cup

Maradona making the defence splitting pass to Claudio Caniggia (top right) for the winning goal against Brazil, 24 June 1990

Maradona captained Argentina again in the 1990 World Cup in Italy to yet another World Cup final. An ankle injury affected his overall performance, and he was much less dominant than four years earlier. After losing their opening game to Cameroon at the San Siro in Milan, Argentina were almost eliminated in the first round, only qualifying in third position from their group. In the round of 16 match against Brazil in Turin, Claudio Caniggia scored the only goal after being set up by Maradona.[98]

In the quarter-final, Argentina faced Yugoslavia in Florence; the match ended 0–0 after 120 minutes, with Argentina advancing in a penalty shootout even though Maradona’s kick, a weak shot to the goalkeeper’s right, was saved. The semi-final against the host nation Italy at Maradona’s club stadium in Naples, the Stadio San Paolo, was also resolved on penalties after a 1–1 draw. This time, however, Maradona was successful with his effort, daringly rolling the ball into the net with an almost exact replica of his unsuccessful kick in the previous round. At the final in Rome, Argentina lost 1–0 to West Germany, the only goal being a penalty by Andreas Brehme in the 85th minute after a controversial foul on Rudi Völler.[98]

1994 World Cup

Maradona going to the drug test after playing v Nigeria, 25 June 1994

At the 1994 World Cup in the United States, Maradona played in only two games (both at the Foxboro Stadium near Boston), scoring one goal against Greece, before being sent home after failing a drug test for ephedrine doping.[99] After scoring against Greece, Maradona had one of the most infamous World Cup goal celebrations as he ran towards one of the sideline cameras shouting with a distorted face and bulging eyes.[100] This turned out to be Maradona’s last international goal for Argentina.[100] In the second game, a 2–1 victory over Nigeria which was to be his last game for Argentina, he set-up both of his team’s goals on free-kicks, the second an assist to Caniggia.

In his autobiography, Maradona argued that the test result was due to his personal trainer giving him the power drink Rip Fuel. His claim was that the U.S. version, unlike the Argentine one, contained the chemical and that, having run out of his Argentine dosage, his trainer unwittingly bought the U.S. formula. FIFA expelled him from USA ’94, and Argentina were subsequently eliminated in the second round by Romania in Los Angeles. Maradona has also separately claimed that he had an agreement with FIFA, on which the organization reneged, to allow him to use the drug for weight loss before the competition in order to be able to play.[101] His failed drugs test at the 1994 World Cup signalled the end of his international career, which had lasted 17 years and yielded 34 goals from 91 games, as well as one winner’s medal and one runners-up medal in the World Cup.[102]

Player profile

Style of play

See also: Creole football

“Diego was capable of things no one else could match. The things I could do with a football, he could do with an orange.”

—Michel Platini, former French midfielder, on Maradona’s ball control[103]

Maradona (pictured dribbling with the ball against Belgium in 1986) had excellent close ball control and would often go on runs taking on the opposition.

Described as a “classic number 10” in the media,[104] Maradona was a traditional playmaker who usually played in a free role, either as an attacking midfielder behind the forwards, or as a second striker in a front–two, although he was also deployed as an offensive–minded central midfielder in a 4–4–2 formation on occasion.[105][106][107][108] Maradona was renowned for his dribbling ability, vision, close ball control, passing and creativity, and is considered one of the most skilful players in the sport.[89][109][110] He had a compact physique, and with his strong legs, low center of gravity, and resulting balance, he could withstand physical pressure well while running with the ball, despite his small stature,[92][111][112] while his acceleration, quick feet, and agility, combined with his dribbling skills and close control at speed, allowed him to change direction quickly, making him difficult for opponents to defend against.[113][114][115][116][117][118] He is regarded by several pundits and football figures as one of the greatest dribblers in the history of the game;[92][111][119][120] former Dutch player Johan Cruyff saw similarities between Maradona and Lionel Messi with the ball seemingly attached to their body when dribbling.[121] His physical strengths were illustrated by his two goals against Belgium in the 1986 World Cup. Although he was known for his penchant for undertaking individual runs with the ball,[122] he was also a strategist and an intelligent team player, with excellent spatial awareness, as well as being highly technical with the ball. He could manage himself effectively in limited spaces, and would attract defenders only to quickly dash out of the melee (as in the second 1986-goal against England),[123][124][125][126][127] or give an assist to a free teammate. Being short, but strong, he could hold the ball long enough with a defender on his back to wait for a teammate making a run or to find a gap for a quick shot. He showed leadership qualities on the field and captained Argentina in their World Cup campaigns of 1986, 1990 and 1994.[128][129] While he was primarily a creative playmaker, Maradona was also known for his finishing and goalscoring ability.[89][130] Former Milan manager Arrigo Sacchi also praised Maradona for his defensive work–rate off the ball in a 2010 interview with Il Corriere dello Sport.[131]

Trading card of Maradona issued by Panini for the 1986 World Cup

The team leader on and off the field – he would speak up on a range of issues on behalf of the players – Maradona’s ability as a player and his overpowering personality had a major positive effect on his team, with his 1986 World Cup teammate Jorge Valdano stating: “Maradona was a technical leader: a guy who resolved all difficulties that may come up on the pitch. Firstly, he was in charge of making the miracles happen, that’s something that gives team-mates a lot of confidence. Secondly, the scope of his celebrity was such that he absorbed all the pressures on behalf of his team-mates. What I mean is: one slept soundly the night before a game not just because you knew you were playing next to Diego and Diego did things no other player in the world could do, but also because unconsciously we knew that if it was the case that we lost then Maradona would shoulder more of the burden, would be blamed more, than the rest of us. That was the kind of influence he exercised on the team.”[132] Lauding the “charisma” of Maradona, another of his Argentina teammates, prolific striker Gabriel Batistuta, stated, “Diego could command a stadium, have everyone watch him. I played with him and I can tell you how technically decisive he was for the team”.[133] Napoli’s former president – Corrado Ferlaino – commented on Maradona’s leadership qualities during his time with the club in 2008, describing him as “a coach on the pitch.”[134]

“Even if I played for a million years, I’d never come close to Maradona. Not that I’d want to anyway. He’s the greatest there’s ever been.”

—Lionel Messi, the player most closely identified with the “New Maradona” label[71]

One of Maradona’s trademark moves was dribbling full-speed on the right wing, and on reaching the opponent’s goal line, delivering accurate passes to his teammates. Another trademark was the rabona, a reverse-cross pass shot behind the leg that holds all the weight.[135] This manoeuvre led to several assists, such as the cross for Ramón Díaz’s header against Switzerland in 1980.[136] He was also a dangerous free kick and penalty kick taker, who was renowned for his ability to bend the ball from corners and direct set pieces.[137][138][139] Regarded as one of the best dead–ball specialists of all time,[140][141][142][143] his free kick technique, which often saw him raise his knee at a high angle when striking the ball, thus enabling him to lift it high over the wall, allowed him to score free kicks even from close range, within 22 to 17 yards (20 to 16 metres) from the goal, or even just outside the penalty area.[144] His style of taking free kicks influenced several other specialists, including Gianfranco Zola,[142] Andrea Pirlo,[145] and Lionel Messi.[146]

Maradona and Lionel Messi (left) depicted in a recreation of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam painting, on a ceiling of a sports club in Barracas, Buenos Aires

Maradona was famous for his cunning personality.[147] Inherent within his nickname “El Pibe de Oro” (“Golden Boy”) is a sense of mischief, with “pibe” being an anti-establishment rogue, street smart and full of guile.[9] Some critics view his controversial “Hand of God” goal at the 1986 World Cup as a clever manoeuvre, with one of the opposition players, Glenn Hoddle, admitting that Maradona had disguised it by flicking his head at the same time as palming the ball.[148] The goal itself has been viewed as an embodiment of the Buenos Aires shanty town Maradona was brought up in and its concept of viveza criolla — “native cunning”.[149] While critical of the illegitimate first goal, England striker Gary Lineker conceded, “When Diego scored that second goal against us, I felt like applauding. I’d never felt like that before, but it’s true… and not just because it was such an important game. It was impossible to score such a beautiful goal. He’s the greatest player of all time, by a long way. A genuine phenomenon.”[103] Maradona used his hand in the 1990 World Cup, again without punishment, and this time on his own goal line, to prevent the Soviet Union from scoring.[150] A number of publications have referred to Maradona as the Artful Dodger, the urchin pickpocket from Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist.[151][152][153][154]

Maradona was dominantly left-footed, often using his left foot even when the ball was positioned more suitably for a right-footed connection.[155] His first goal against Belgium in the 1986 World Cup semi-final is a worthy indicator of such; he had run into the inside right channel to receive a pass but let the ball travel across to his left foot, requiring more technical ability. During his run past several England players in the previous round for the “Goal of the Century” he did not use his right foot once, despite spending the whole movement on the right-hand side of the pitch. In the 1990 World Cup second round tie against Brazil, he did use his right foot to set up the winning goal for Claudio Caniggia due to two Brazilian markers forcing him into a position that made use of his left foot less practical.[156]

Reception

Pelé scored more goals. Lionel Messi has won more trophies. Both have lived more stable lives than the overweight former cocaine addict who tops this list, whose relationship with football became increasingly strained the longer his career continued. If you’ve seen Diego Maradona with a football at his feet, you’ll understand.

— Andrew Murray on Maradona topping FourFourTwo magazine’s “100 Greatest Footballers Ever” list, July 2017.[157]

Regarded as the best player of his generation,[125] as well as one of the greatest players of all time by several pundits, players, and managers, and by some as the best player ever,[8][71][157][158][159][160][161] Maradona is renowned as one of the most skilful players in the history of football,[89][109][110] as well as being considered one of the greatest dribblers[92][111][119][120] and free kick takers in the history of the sport.[140][141][142][143] Considered to be a precocious talent in his youth,[9] in addition to his playing ability, Maradona also drew praise from his former manager Menotti for his dedication, determination, and the work-ethic he demonstrated in order to improve the technical aspect of his game in training, despite his natural gifts, with the manager noting: “I’m always cautious about using the word ‘genius’. I find it hard to apply that even to Mozart. The beauty of Diego’s game has a hereditary element – his natural ease with the ball – but it also owes a lot to his ability to learn: a lot of those brushstrokes, those strokes of ‘genius’, are in fact a product of his hard work. Diego worked very hard to be the best.”[162] Maradona’s former Napoli manager – Ottavio Bianchi – also praised his discipline in training, commenting: “Diego is different to the one that they depict. When you got him on his own he was a very good kid. It was beautiful to watch him and coach him. They all speak of the fact that he did not train, but it was not true because Diego was the last person to leave the pitch, it was necessary to send him away because otherwise he would stay for hours to invent free kicks.”[163] However, although, as Bianchi noted, Maradona was known for making “great plays” and doing “unimaginable” and “incredible things” with the ball during training sessions,[164][165][166] and would even go through periods of rigorous exercise, he was equally known for his limited work-rate in training without the ball, and even gained a degree of infamy during his time in Italy for missing training sessions with Napoli, while he often trained independently instead of with his team.[164][167][168][169][170][171]

In a 2019 documentary film on his life, Maradona confessed that his weekly regime consisted of “playing a game on Sunday, going out until Wednesday, then hitting the gym on Thursday.” Regarding his inconsistent training regimen, the film’s director, Asif Kapadia, commented in 2020: “He had a metabolism. He would look so incredibly out of shape, but then he’d train like crazy and sweat it off by the time matchday came along. His body shape just didn’t look like a footballer, but then he had this ability and this balance. He had a way of being, and that idea of talking to him honestly about how a typical week transpired was pretty amazing.” He also revealed that Maradona was ahead of his time in the fact that he had a personal fitness coach – Fernando Signorini – who trained him in a variety of areas, in addition to looking after his physical conditioning, adding: “While he [Maradona] was in a football team he had his own regime. How many players would do that? How many players would even know to think like that? ‘I’m different to anyone else so I need to train at what I’m good at and what I’m weak at.’ Signorini is very well read and very intelligent. He would literally say, ‘This is the way I’m going to train you, read this book.’ He would help him psychologically, talk to him about philosophy, and things like that.”[167][172] Moreover, Maradona was notorious for his poor diet and extreme lifestyle off the pitch, including his use of illicit drugs and alcohol abuse, which along with personal issues, his metabolism, medication that he was prescribed, and periods of inactivity due to injuries and suspensions, led to his significant weight–gain and physical decline as his career progressed; his lack of discipline and difficulties in his turbulent personal life are thought by some in the sport to have negatively impacted his performances and longevity in the later years of his playing career.[123][162][173]

A controversial footballing figure, while he earned critical acclaim from players, pundits, and managers over his playing style, he also drew criticism in the media for his temper and confrontational behaviour, both on and off the pitch.[164][173][174][175][176][177] However, in 2005, Paolo Maldini, described Maradona both as the greatest player he ever faced, and also as the most honest, stating: “He was a model of good behaviour on the pitch – he was respectful of everyone, from the great players down to the ordinary team member. He was always getting kicked around and he never complained – not like some of today’s strikers.”[178] His former defensive club and international teammate, Baresi, stated when he was asked who was his greatest opponent: “Maradona; when he was on form, there was almost no way of stopping him,”[56] while fellow former Italy defender Giuseppe Bergomi described Maradona as the greatest player of all time in 2018.[179]

In 1999, Maradona was placed second behind Pelé by World Soccer in the magazine’s list of the “100 Greatest Players of the 20th Century.”[180] Along with Pelé, Maradona was one of the two joint winners of the “FIFA Player of the Century” award in 2000,[7] and also placed fifth in “IFFHS’ Century Elections.”[181] In a 2014 FIFA poll, Maradona was voted the second-greatest number 10 of all-time, behind only Pelé,[182] and later that year, was ranked second in The Guardian’s list of the 100 greatest World Cup players of all-time, ahead of the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, once again behind Pelé.[183] In 2017, FourFourTwo ranked him in first place in their list of “100 greatest players,”[157] while in 2018, he was ranked in first place by the same magazine in their list of the “Greatest Football Players in World Cup History”;[184] in March 2020, he was also ranked first by Jack Gallagher of 90min.com in their list of “Top 50 Greatest Players of All Time.”[185] In May 2020, Sky Sports ranked him as the best player ever never to have won the Champions League or European Cup.[186]

Retirement and tributes

Diego Maradona’s blaugrana shirt on display in the FC Barcelona Museum

Hounded for years by the press, Maradona once fired a compressed-air rifle at reporters who he claimed were invading his privacy. This quote from former teammate Jorge Valdano summarizes the feelings of many:

He is someone many people want to emulate, a controversial figure, loved, hated, who stirs great upheaval, especially in Argentina… Stressing his personal life is a mistake. Maradona has no peers inside the pitch, but he has turned his life into a show, and is now living a personal ordeal that should not be imitated.[187]

In 1990, the Konex Foundation from Argentina granted him the Diamond Konex Award, one of the most prestigious culture awards in Argentina, as the most important personality in Sports in the last decade in his country. In April 1996, Maradona had a three-round exhibition boxing match with Santos Laciar for charity.[188] In 2000, Maradona published his autobiography Yo Soy El Diego (“I am The Diego”), which became a best-seller in Argentina.[189] Two years later, Maradona donated the Cuban royalties of his book to “the Cuban people and Fidel”.[190]

Maradona at the Soccer Aid charity game at Old Trafford, Manchester in May 2006, after losing weight

In 2000, he won FIFA Player of the Century award which was to be decided by votes on their official website, their official magazine and a grand jury. Maradona won the Internet-based poll, garnering 53.6% of the votes against 18.53% for Pelé.[191] In spite of this, and shortly before the ceremony, FIFA added a second award and appointed a “Football Family” committee composed of football journalists that also gave to Pelé the title of best player of the century to make it a draw. Maradona also came fifth in the vote of the IFFHS (International Federation of Football History and Statistics).[181] In 2001, the Argentine Football Association (AFA) asked FIFA for authorization to retire the jersey number 10 for Maradona. FIFA did not grant the request, even though Argentine officials have maintained that FIFA hinted that it would.[192]

Maradona has topped a number of fan polls, including a 2002 FIFA poll in which his second goal against England was chosen as the best goal ever scored in a World Cup; he also won the most votes in a poll to determine the All-Time Ultimate World Cup Team. On 22 March 2010, Maradona was chosen number 1 in The Greatest 10 World Cup players of all time by the London-based newspaper The Times.[193] Argentinos Juniors named its stadium after Maradona on 26 December 2003. In 2003, Maradona was employed by the Libyan footballer Al-Saadi Gaddafi, the third son of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, as a “technical consultant”, while Al-Saadi was playing for the Italian club, Perugia, which was playing in Serie A at the time.[194]

Maradona in Kolkata, India, in December 2008. Maradona laid the foundation stone for a football academy in the eastern suburbs of the city, and was greeted by over 100,000 fans in Salt Lake Stadium.[195]

On 22 June 2005, it was announced that Maradona would return to former club Boca Juniors as a sports vice-president in charge of managing the First Division roster (after a disappointing 2004–05 season, which coincided with Boca’s centenary).[196] His contract began 1 August 2005, and one of his first recommendations proved to be very effective: advising the club to hire Alfio Basile as the new coach. With Maradona fostering a close relationship with the players, Boca won the 2005 Apertura, the 2006 Clausura, the 2005 Copa Sudamericana and the 2005 Recopa Sudamericana.

On 15 August 2005, Maradona made his debut as host of a talk-variety show on Argentine television, La Noche del 10 (“The Night of the no. 10”). His main guest on opening night was Pelé; the two had a friendly chat, showing no signs of past differences. However, the show also included a cartoon villain with a clear physical resemblance to Pelé. In subsequent evenings, he led the ratings on all occasions but one. Most guests were drawn from the worlds of football and show business, including Ronaldo and Zinedine Zidane, but also included interviews with other notable friends and personalities such as Cuban leader Fidel Castro and boxers Roberto Durán and Mike Tyson.[197] Maradona gave each of his guests a signed Argentina jersey, which Tyson wore when he arrived in Brazil, Argentina’s biggest rivals.[198] In November 2005, however, Maradona rejected an offer to work with Argentina’s national football team.[199]

In May 2006, Maradona agreed to take part in UK’s Soccer Aid (a program to raise money for UNICEF).[200] In September 2006, Maradona, in his famous blue and white number 10, was the captain for Argentina in a three-day World Cup of Indoor Football tournament in Spain. On 26 August 2006, it was announced that Maradona was quitting his position in the club Boca Juniors because of disagreements with the AFA, who selected Alfio Basile to be the new coach of the Argentina national team.[201] In 2008, award-winning Serbian filmmaker Emir Kusturica made a documentary about Maradona’s life, entitled Maradona.[202]

On 1 September 2014, Maradona, along with many current and former footballing stars, took part in the “Match for Peace”, which was played at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome, with the proceeds being donated entirely to charity.[203] Maradona set up a goal for Roberto Baggio during the first half of the match, with a chipped through-ball over the defence with the outside of his left foot.[204] Unusually, both Baggio and Maradona wore the number 10 shirt, despite playing on the same team.[204] On 17 August 2015, Maradona visited Ali Bin Nasser, the Tunisian referee of the Argentina–England quarter-final match at the 1986 World Cup where Maradona scored his Hand of God, and paid tribute to him by giving him a signed Argentine jersey.[205][206]

Managerial career

Club management

Maradona in Al Karama, United Arab Emirates in 2011 after being appointed manager of Dubai club Al Wasl FC

Maradona began his managerial career alongside former Argentinos Juniors midfield teammate Carlos Fren. The pair led Mandiyú of Corrientes in 1994 and Racing Club in 1995, with little success. In May 2011 he became manager of Dubai club Al Wasl FC in the United Arab Emirates. Maradona was sacked on 10 July 2012.[207][208] In August 2013, Maradona moved on to become mental coach at Argentine club Deportivo Riestra. Maradona departed this role in 2017 to become the head coach of Fujairah, in the UAE second division, before leaving at the end of the season upon failure to secure promotion at the club.[12] In September 2018 he was appointed manager of Mexican second division side Dorados.[15] He made his debut with Dorados on 17 September 2018 with a 4–1 victory over Cafetaleros de Tapachula.[209] On 13 June 2019, after Dorados failed to clinch promotion to the Mexican top flight, Maradona’s lawyer announced that he would be stepping down from the role, citing health reasons.[210]

On 5 September 2019, Maradona was unveiled as the new head coach of Gimnasia de La Plata, signing a contract until the end of the season.[16] After two months in charge he left the club on 19 November.[211] However, two days later, Maradona rejoined the club as manager saying that “we finally achieved political unity in the club”.[212] Maradona insisted that Gabriel Pellegrino remain club President if he were to stay with Gimnisia de La Plata.[213][214] However it was still not clear if Pellegrino, who declined to run for re-election,[213][214] would stay on as club President.[213][214] Originally scheduled to be held on 23 November 2019,[213] the election was delayed 15 days.[214] On 15 December 2019, Pellegrino, who was encouraged by Maradona to seek re-election, was re-elected to a three-year term.[215] Despite having a bad record during the 2019–20 season, Gimnasia renewed Maradona’s contract on 3 June 2020 through the 2020–21 season.[216]

International management

After the resignation of Argentina national team coach Alfio Basile in 2008, Maradona immediately proposed his candidacy for the vacant role. According to several press sources, his major challengers included Diego Simeone, Carlos Bianchi, Miguel Ángel Russo and Sergio Batista. On 29 October 2008, AFA chairman Julio Grondona confirmed that Maradona would be the head coach of the national team. On 19 November 2008, Maradona managed Argentina for the first time when they played against Scotland at Hampden Park in Glasgow, which Argentina won 1–0.[217]

Maradona as coach of Argentina in 2009. He left the position after the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa.

After winning his first three matches in charge of the national team, he oversaw a 6–1 defeat to Bolivia, equalling the team’s worst ever margin of defeat. With two matches remaining in the qualification tournament for the 2010 World Cup, Argentina was in fifth place and faced the possibility of failing to qualify, but victory in the last two matches secured qualification for the finals.[218][219] After Argentina’s qualification, Maradona used abusive language at the live post-game press conference, telling members of the media to “suck it and keep on sucking it”.[220] FIFA responded with a two-month ban on all footballing activity, which expired on 15 January 2010, and a CHF 25,000 fine, with a warning as to his future conduct.[221] The friendly match scheduled to take place at home to the Czech Republic on 15 December, during the period of the ban, was cancelled. The only match Argentina played during Maradona’s ban was a friendly away to Catalonia, which they lost 4–2.

At the World Cup finals in June 2010, Argentina started by winning 1–0 against Nigeria, followed by a 4–1 victory over South Korea on the strength of a Gonzalo Higuaín hat-trick.[222][223] In the final match of the group stage, Argentina won 2–0 against Greece to win the group and advance to a second round, meeting Mexico.[224] After defeating Mexico 3–1, however, Argentina was routed by Germany 4–0 in the quarter-finals to go out of the competition.[225] Argentina was ranked fifth in the tournament. After the defeat to Germany, Maradona admitted that he was considering his future as Argentina coach, stating, “I may leave tomorrow.”[226] On 15 July 2010, the AFA said that he would be offered a new four-year deal that would keep him in charge through to the summer of 2014 when Brazil stages the World Cup.[227] On 27 July, however, the AFA announced that its board had unanimously decided not to renew his contract, different to 1978 World Cup winning captain and 1986 teammate, Daniel Passarella.[228] Afterwards, on 29 July, Maradona claimed that AFA president Julio Grondona and director of national teams (as well as his former Argentine national team and Sevilla coach) Carlos Bilardo had “lied to”, “betrayed” and effectively sacked him from the role. He said, “They wanted me to continue, but seven of my staff should not go on, if he told me that, it meant he did not want me to keep working.”[229]

Personal life

Family

Having returned to his Catholic faith, Maradona donated a signed Argentina jersey to Pope Francis, and it is kept in one of the Vatican Museums.

Born to a Roman Catholic family, his parents were Diego Maradona Senior and Dalma Salvadora Franco. Maradona married long-time fiancée Claudia Villafañe on 7 November 1984 in Buenos Aires, and they had two daughters, Dalma Nerea (born 2 April 1987) and Gianinna Dinorah (born 16 May 1989), by whom he became a grandfather in 2009.[230]

Maradona and Villafañe divorced in 2004. Daughter Dalma has since asserted that the divorce was the best solution for all, as her parents remained on friendly terms. They travelled together to Naples for a series of homages in June 2005 and were seen together on other occasions, including the Argentina games during 2006 World Cup.[231]

During the divorce proceedings, Maradona admitted he is the father of Diego Sinagra (born in Naples on 20 September 1986). The Italian courts had already ruled so in 1993, after Maradona refused to undergo DNA tests to prove or disprove his paternity. Diego Junior met Maradona for the first time in May 2003 after tricking his way onto a golf course in Italy where Maradona was playing.[232] Sinagra is now a footballer playing in Italy.[233] After the divorce, Claudia embarked on a career as a theatre producer, and Dalma was seeking an acting career; she had expressed her desire to attend the Actor’s Studio in Los Angeles.[234][235]

Maradona’s relationship with his immediate family was a close one, and in a 1990 interview with Sports Illustrated he showed phone bills where he had spent a minimum of 15,000 US dollars per month calling his parents and siblings.[236] Maradona’s mother, Dalma, died on 19 November 2011. He was in Dubai at the time, and desperately tried to fly back in time to see her, but was too late. She was 81 years old. His father, “Don” Diego, died on 25 June 2015 at age 87.[237]

Maradona’s great-nephew, Hernán, is a professional footballer.[238]

Drug abuse and health issues

From the mid-1980s until 2004, Maradona was addicted to cocaine. He allegedly began using the drug in Barcelona in 1983.[239] By the time he was playing for Napoli, he had a regular addiction, which began to interfere with his ability to play football.[240] In the midst of his drug-crisis in 1991 Maradona was asked by journalists if the hit song Mi enfermedad (lit. My Disease) was dedicated to him.[241]

Maradona had a tendency to put on weight and suffered increasingly from obesity, at one point weighing 280 lb (130 kg). He was obese from the end of his playing career until undergoing gastric bypass surgery in a clinic in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, on 6 March 2005. His surgeon said that Maradona would follow a liquid diet for three months in order to return his normal weight.[242] When Maradona resumed public appearances shortly thereafter, he displayed a notably thinner figure.[243]

On 29 March 2007, Maradona was readmitted to a hospital in Buenos Aires. He was treated for hepatitis and effects of alcohol abuse and was released on 11 April, but readmitted two days later.[244] In the following days, there were constant rumours about his health, including three false claims of his death within a month.[245] After transfer to a psychiatric clinic specializing in alcohol-related problems, he was discharged on 7 May.[246] On 8 May 2007, Maradona appeared on Argentine television and stated that he had quit drinking and had not used drugs in two and a half years.[247] In January 2019, Maradona underwent surgery after a hernia caused internal bleeding in his stomach.[248]

Political views

Maradona presenting a signed shirt to the former President of Argentina Néstor Kirchner in December 2007

Having previously been vocal in his support of neoliberal Argentine President Carlos Menem and his Harvard University–educated economist Domingo Cavallo, Maradona has shown sympathy to left-wing ideologies. He became friends with Cuban leader Fidel Castro while receiving treatment on the island, with Castro stating, “Diego is a great friend and very noble, too. There’s also no question he’s a wonderful athlete and has maintained a friendship with Cuba to no material gain of his own.”[71] Maradona had a portrait of Castro tattooed on his left leg and one of Fidel’s second in command, fellow Argentine Che Guevara on his right arm.[249] In his autobiography, El Diego, he dedicated the book to various people, including Castro. He wrote, “To Fidel Castro and, through him, all the Cuban people.”[250]

Maradona, then-president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and Evo Morales, at the funeral of former President of Argentina Néstor Kirchner, 28 October 2010

Maradona was also a supporter of former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez. In 2005, he came to Venezuela to meet Chávez, who received him in the Miraflores Palace. After this meeting, Maradona claimed that he had come with the aim of meeting a “great man” (“un grande” in Spanish), but he had met instead a gigantic man (“un gigante” in Spanish, meaning he was more than great). “I believe in Chávez, I am Chavista. Everything Fidel does, everything Chávez does, for me is the best.”[251] Maradona was the guest of honour of Chávez at the opening game of the 2007 Copa América held in Venezuela.[252]

Maradona declared his opposition to what he identifies as imperialism, particularly during the 2005 Summit of the Americas in Mar del Plata, Argentina. There he protested George W. Bush’s presence in Argentina, wearing a T-shirt labelled “STOP BUSH” (with the “s” in “Bush” being replaced with a swastika) and referring to Bush as “human garbage”.[253][254] In August 2007, Maradona went further, making an appearance on Chávez’s weekly television show Alo Presidente and saying, “I hate everything that comes from the United States. I hate it with all my strength.”[255] In December 2008, however, Maradona had adopted a more pro-US attitude when he expressed admiration for Bush’s successor, President-elect Barack Obama, and held great expectations for him.[195]

“I asked myself, ‘Who is this man? Who is this footballing magician, this Sex Pistol of international football, this cocaine victim who kicked the habit, looked like Falstaff and was as weak as spaghetti?’ If Andy Warhol had still been alive, he would have definitely put Maradona alongside Marilyn Monroe and Mao Tse-tung. I’m convinced that if he hadn’t been a footballer, he’d’ve become a revolutionary.”

—Emir Kusturica, film director[71]

With his poor shanty town upbringing, Maradona has cultivated a man-of-the-people persona.[256] During a meeting with Pope John Paul II at the Vatican in 1987, they clashed on the issue of wealth disparity, with Maradona stating, “I argued with him because I was in the Vatican and I saw all these golden ceilings and afterwards I heard the Pope say the Church was worried about the welfare of poor kids. Sell your ceiling then amigo, do something!”[256] In September 2014, Maradona met with Pope Francis in Rome, crediting Francis for inspiring him to return to religion after many years; he stated, “We should all imitate Pope Francis. If each one of us gives something to someone else, no one in the world would be starving.”[257]

In December 2007, Maradona presented a signed shirt with a message of support to the people of Iran: it is displayed in the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ museum.[258] In April 2013, Maradona visited the tomb of Hugo Chávez and urged Venezuelans to elect the late leader’s designated successor, Nicolás Maduro, to continue the socialist leader’s legacy; “Continue the struggle,” Maradona said on television.[259] Maradona attended Maduro’s final campaign rally in Caracas, signing footballs and kicking them to the crowd, and presented Maduro with an Argentina jersey.[259] Having visited Chávez’s tomb with Maradona, Maduro said, “Speaking with Diego was very emotional because comandante Chávez also loved him very much.”[259] Maradona participated and danced at the electoral campaign rally during the 2018 presidential elections in Venezuela.[260][261] During the 2019 Venezuelan presidential crisis, the Mexican Football Federation fined him for violating their code of ethics and dedicating a team victory to Nicolás Maduro.[262]

In October 2015, Maradona thanked Queen Elizabeth II and the Houses of Parliament in London for giving him the chance to provide “true justice” as head of an organization designed to help young children.[263] In a video released on his official Facebook page, Maradona confirmed he would accept their nomination for him to become Latin American director for the non-governmental organization Football for Unity.[263]

Financial problems

In March 2009, Italian officials announced that Maradona still owed the Italian government €37 million in local taxes, €23.5 million of which was accrued interest on his original debt. They reported that thus far, Maradona had paid only €42,000, two luxury watches and a set of earrings.[264][265]

Death

On 2 November 2020, Maradona was admitted to a hospital in La Plata, supposedly for psychological reasons. A representative of the ex-footballer said his condition was not serious.[266] A day later, he underwent emergency brain surgery to treat a subdural hematoma.[267] He was released on 12 November after successful surgery and was supervised by doctors as an outpatient.[268][269] On 25 November 2020, at the age of 60, Maradona died of a heart attack at his home in Tigre, Buenos Aires, Argentina. In a statement on social media, the Argentine Football Association expressed “its deepest sorrow for the death of our legend”, adding: “You will always be in our hearts.”[270] President Alberto Fernández announced three days of national mourning.[271]

In popular culture

Religious display of Maradona in Naples, Italy

The American newspaper The Houston Chronicle wrote about Maradona:

To understand the gargantuan shadow Maradona casts over his football-mad homeland, one has to conjure up the athleticism of Michael Jordan, the power of Babe Ruth – and the human fallibility of Mike Tyson. Lump them together in a single barrel-chested man with shaggy black hair and you have El Diego, idol to the millions who call him D10S, a mashup of his playing number and the Spanish word for God.[272]

In Argentina, Maradona is considered a sports hero. On the idolatry that exists in Argentina, former teammate Jorge Valdano said, “At the time that Maradona retired from active football, left traumatized Argentina. Maradona was more than just a great footballer. It was a special compensation factor for a country that in a few years lived several military dictatorships and social frustrations of all kinds”.[273] Valdano added that “Maradona offered to the Argentines a way out of their collective frustration, and that’s why people love him. There is a divine figure.”[273]

Three icons of Argentina statues: tango pioneer Carlos Gardel, political leader Eva Perón, and Maradona

Ever since 1986, it is common for Argentines abroad to hear Maradona’s name as a token of recognition, even in remote places.[39] The Tartan Army sing a version of the Hokey Cokey in honour of the Hand of God goal against England.[274] In Argentina, Maradona is often talked about in terms reserved for legends. In the Argentine film El Hijo de la Novia (“Son of the Bride”), somebody who impersonates a Catholic priest says to a bar patron, “They idolized him and then crucified him.” When a friend scolds him for taking the prank too far, the fake priest retorts, “But I was talking about Maradona.” He is the subject of the film El Camino de San Diego, though he himself only appears in archive footage.

Maradona was included in many cameos in the Argentine comic book El Cazador de Aventuras. After the closing of it, the authors started a new short-lived comic book titled “El Die”, using Maradona as the main character. Maradona has had several online Flash games that are entirely dedicated to his legacy.[275] In Rosario, Argentina, locals organized the parody religion of the “Church of Maradona”. The organization reformulates many elements from Christian tradition, such as Christmas or prayers, reflecting instead details from Maradona. It had 200 founding members, and tens of thousands more have become members via the church’s official web site.[276]

Maradona (middle) with Queen during the rock band’s 1981 South American tour

Many Argentine artists performed songs in tribute to Diego, such as “La Mano de Dios” by El Potro Rodrigo, “Maradona” by Andrés Calamaro, “Para siempre Diego” (Diego forever) by Los Ratones Paranoicos, “Francotirador” (Sniper) by Attaque 77, “Maradona blues” by Charly García, “Santa Maradona” (Saint Maradona) by Mano Negra, “La Vida Tombola” by Manu Chao, among others. There are also films, such as: Maradona, La Mano de Dios (Maradona, the Hand of God), El Camino de San Diego (Saint Diego’s Road), Amando a Maradona (Loving Maradona), Maradona by Kusturica.[202]

By 1982, Maradona had become one of the biggest sports stars in the world and had endorsements with many companies, including Puma and Coca-Cola, earning him an additional $1.5 million per year on top of his club salary.[277] In 1982, he featured in a World Cup commercial for Coca-Cola, and a Japanese commercial for Puma.[277] In 2010 he appeared in a commercial for French fashion house Louis Vuitton, indulging in a game of table football with fellow World Cup winners Pelé and Zinedine Zidane.[278] Maradona features in the music video to the 2010 World Cup song “Waka Waka” by Shakira, with footage shown of him celebrating Argentina winning the 1986 World Cup.[279]

Banners depicting Maradona – such as this where he features alongside Lionel Messi at the 2018 World Cup – often appear at Argentina games.

A 2006 television commercial for Brazilian soft drink Guaraná Antarctica portrayed Maradona as a member of the Brazil national team, including wearing the yellow jersey and singing the Brazilian national anthem with Brazilian players Ronaldo and Kaká.[280] Later on in the commercial he wakes up realizing it was a nightmare after having drunk too much of the drink. This generated some controversy in the Argentine media after its release (although the commercial was not supposed to air on the Argentine market, fans could see it online). Maradona replied that he has no problem in wearing the Brazilian national squad jersey despite Argentina and Brazil having a tense rivalry in football, but that he would refuse to wear the shirt of River Plate, Boca Juniors’ traditional rival.[281] There is a documented phenomenon of Brazilians being named in honour of Maradona,[282] an example being footballer Diego Costa.[283]

In 2017, Maradona featured as a legendary player in the football video games FIFA 18 and Pro Evolution Soccer 2018.[284] In 2019, a documentary film titled Diego Maradona was released by Academy Award and BAFTA Award winning filmmaker Asif Kapadia, director of Amy (on singer Amy Winehouse) and Senna (on motor racing driver Ayrton Senna). Kapadia states, “Maradona is the third part of a trilogy about child geniuses and fame.”[285] He added, “I was fascinated by his journey, wherever he went there were moments of incredible brilliance and drama. He was a leader, taking his teams to the very top, but also many lows in his career. He was always the little guy fighting against the system… and he was willing to do anything, to use all of his cunning and intelligence to win.”[286]

Career statistics

Maradona made 694 appearances and scored 354 goals for club and country combined, with a goalscoring average of 0.51.

Club

Club Season League Cup Continental Other Total

Division Apps Goals Apps Goals Apps Goals Apps Goals Apps Goals

Argentinos Juniors[53] 1976 Primera División 11 2 – – – 11 2

1977 49 19 – – – 49 19

1978 35 26 – – – 35 26

1979 26 26 – – – 26 26

1980 45 43 – – – 45 43

Total 166 116 – – – 166 116

Boca Juniors[53] 1981 Primera División 40 28 – – – 40 28

Barcelona[53] 1982–83 La Liga 20 11 5[a] 3 4[b] 5 6[c] 4 35 23

1983–84 16 11 4[d] 1 3[e] 3 – 23 15

Total 36 22 9 4 7 8 6 4 58 38

Napoli[53] 1984–85 Serie A 30 14 6[f] 3 – – 36 17

1985–86 29 11 2[g] 2 – – 31 13

1986–87 29 10 10[h] 7 2[i] 0 – 41 17

1987–88 28 15 9[j] 6 2[k] 0 – 39 21

1988–89 26 9 12[l] 7 12[m] 3 – 50 19

1989–90 28 16 3[n] 2 5[o] 0 – 36 18

1990–91 18 6 3[p] 2 4[q] 2 1[r] 0 26 10

Total 188 81 45 29 25 5 1 0 259 115

Sevilla[53] 1992–93 La Liga 26 5 3[s] 3 – – 29 8

Newell’s Old Boys[53] 1993–94 Primera División 5 0 – – – 5 0

Boca Juniors[53] 1995–96 24 5 – – – 24 5

1996–97 1 0 – – 1[t] 0 2 0

1997–98 5 2 – – – 5 2

Total 70 35 – – 1 0 71 35

Career total 491 259 57 36 32 13 8 4 588 312

Notes

Appearances in the 1982–83 Copa del Rey

Appearances in the 1982–83 European Cup Winners’ Cup

Appearances in the 1983 Copa de la Liga

Appearances in the 1983–84 Copa del Rey

Appearances in the 1983–84 European Cup Winners’ Cup

Appearances in the 1984–85 Coppa Italia

Appearances in the 1985–86 Coppa Italia

Appearances in the 1986–87 Coppa Italia

Appearances in the 1986–87 UEFA Cup

Appearances in the 1987–88 Coppa Italia

Appearances in the 1987–88 European Cup

Appearances in the 1988–89 Coppa Italia

Appearances in the 1988–89 UEFA Cup

Appearances in the 1989–90 Coppa Italia

Appearances in the 1989–90 UEFA Cup

Appearances in the 1990–91 Coppa Italia

Appearances in the 1990–91 European Cup

Appearance in the 1990 Supercoppa Italiana

Appearances in the 1992–93 Copa del Rey

Appearance in the 1997 Supercopa Libertadores

International

For a comprehensive listing of international goals scored by Diego Maradona, see List of international goals scored by Diego Maradona.

Appearances and goals by national team, year and competition

Team Year Competitive Friendly Total

Apps Goals Apps Goals Apps Goals

Argentina U20[287] 1977 3[a] 0 – 3 0

1978 – – –

1979 11[b] 7 1 1 12 8

Total 14 7 1 1 15 8

Argentina[53][70] 1977 – 3 0 3 0

1978 – 1 0 1 0

1979 2[c] 1 6 2 8 3

1980 – 10 7 10 7

1981 2[d] 1 – 2 1

1982 5[e] 2 5 0 10 2

1983 – – –

1984 – – –

1985 6[f] 3 4 3 10 6

1986 7[g] 5 3 2 10 7

1987 4[h] 3 2 1 6 4

1988 2[i] 1 1 0 3 1

1989 6[j] 0 1 0 7 0

1990 7[k] 0 3 1 10 1

1991 – – –

1992 – – –

1993 3[l] 0 1 0 4 0

1994 2[m] 1 5 1 7 2

Total 46 17 45 17 91 34

Career total 60 24 46 18 106 42

Notes

Appearances in the 1977 South American U-20 Championship

Five appearances and one goal in the 1979 South American U-20 Championship, six appearances and six goals in the 1979 FIFA World Youth Championship

Appearances in the 1979 Copa América

Appearances in the 1980 Mundialito

Appearances in the 1982 World Cup

Appearances in the 1986 FIFA World Cup qualification

Appearances in the 1986 World Cup

Appearances in the 1987 Copa América

Appearances in the Four Nations Tournament

Appearances in the 1989 Copa América

Appearances in the 1990 World Cup

One appearance in the Artemio Franchi Trophy, two appearances in the 1994 FIFA World Cup qualification

Appearances in the 1994 World Cup

Managerial statistics

Team Nat From To Record

G W D L Win %

Textil Mandiyú Argentina January 1994 June 1994 12 1 6 5 8.33

Racing Club Argentina May 1995 November 1995 11 2 6 3 18.18

Argentina Argentina November 2008 July 2010 24 18 0 6 75.00

Al-Wasl United Arab Emirates May 2011 July 2012 23 11 3 9 47.83

Fujairah United Arab Emirates April 2017 April 2018 11 7 3 1 63.64

Dorados Mexico September 2018 June 2019 38 20 9 9 52.63

Gimnasia de La Plata Argentina September 2019 November 2020 21 8 4 9 38.10

Total 140 67 31 42 47.86

Honours

Club

Boca Juniors[288]

Argentine Primera División: 1981 Metropolitano

Barcelona[288]

Copa del Rey: 1983

Copa de la Liga: 1983

Supercopa de España: 1983

Napoli[288]

Serie A: 1986–87, 1989–90

Coppa Italia: 1986–87

UEFA Cup: 1988–89

Supercoppa Italiana: 1990

International

Argentina Youth[288]

FIFA World Youth Championship: 1979

Argentina[288][289]

FIFA World Cup: 1986

Artemio Franchi Trophy: 1993

Individual

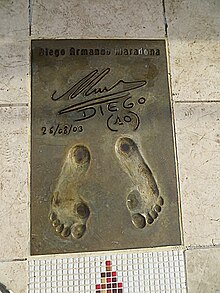

Maradona’s Golden Foot award in “The Champions Promenade” on the seafront of the Principality of Monaco

Argentine Primera División top scorers: 1978 Metropolitano, 1979 Metropolitano, 1979 Nacional, 1980 Metropolitano, 1980 Nacional[290]

FIFA World Youth Championship Golden Ball: 1979[68]

FIFA World Youth Championship Silver Shoe: 1979[68]

Argentine Football Writers’ Footballer of the Year: 1979, 1980, 1981, 1986[291]

South American Footballer of the Year: (official award) 1979, 1980[290]

Olimpia de Oro: 1979, 1986[292]

Guerin d’Oro (Serie A Footballer of the Year): 1985[293]

UNICEF European Footballer of the Season: 1989–90[294]

FIFA World Cup Golden Ball: 1986[290]

FIFA World Cup Silver Shoe: 1986

FIFA World Cup Most Assists: 1986[295]

FIFA World Cup All-Star Team: 1986, 1990

Onze d’Or: 1986, 1987[296]

L’Équipe Champion of Champions: 1986

United Press International Athlete of the Year Award: 1986

World Soccer magazine’s Player of the Year: 1986

Capocannoniere (Serie A top scorer): 1987–88[290]

Coppa Italia top scorer: 1987–88

FIFA World Cup Bronze Ball: 1990[290]

FIFA World Cup All-Time Team: 1994[297]

South American Team of the Year: 1995[298]

Ballon d’Or for services to football (France Football): 1995[299]

World Team of the 20th Century: 1998[290]

World Soccer magazine’s Greatest Players of the 20th century: (#2) 1999[180]

Argentine Sports Writers’ Sportsman of the Century: 1999

Marca Leyenda: 1999[300]

Number 10 retired by Napoli football team as a recognition to his contribution to the club: 2000[301]

FIFA Player of the Century: 2000[290]

FIFA Goal of the Century (for his second goal against England in 1986 FIFA World Cup quarter-final): 2002[290]

FIFA World Cup Dream Team: 2002[302]

Golden Foot: 2003, as football legend[303]

FIFA 100 Greatest Living Players: 2004[290]

Argentine Senate “Domingo Faustino Sarmiento” recognition for lifetime achievement: 2005

Greatest Footballers in World Cup History: No. 1, by The Times, 2010[304]

Best Athlete in History: No. 1, by Corriere dello Sport – Stadio, 2012[305]

Globe Soccer Awards Player Career Award: 2012[306]

World Soccer magazine’s Greatest XI of all time: 2013[307]

Greatest Football Players of All-Time: No. 1 by FourFourTwo magazine, 2017[157]