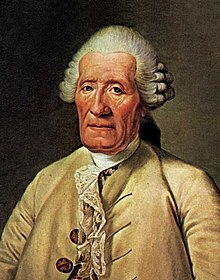

جاك دو فوكانسون..ابن صانع القفازات الذي صنع أول انسان آلي

حسب آخر إحصائيات الاتحاد الدولي للروبوتات، يوجد حاليا أكثر من 2.4 مليون روبوت يعمل في قطاع الصناعة في جميع أنحاء العالم. وقد بلغت قيمة المبيعات العالمية للروبوت رقما قياسيا جديدا بلغ 16.5 مليار دولار أمريكي. فمجال الروبوتات هو أحد أهم مجالات المستقبل، فالروبوت يمكنه القيام بمهام عسكرية وصناعية ومنزلية ويمكنه أيضا عزف الموسيقى.

هذا الابتكار العظيم يرجع الفضل فيه للمهندس والمبتكر الفرنسي الفذ، جاك دو فوكانسون الذي ولد في شهر فبراير من عام 1709 في مدينة جرونوبل الفرنسية. كان الأخ الأصغر لتسعة من الأخوة والأخوات وكانت والدته الكاثوليكية المتدينة تصحبه معها أثناء ذهابها للأعتراف في الكنيسة فكان الطفل ينتظر في الغرفة المجاورة يتفحص الساعة الموجودة في الغرفة والآلية الميكانيكية الخاصة بها حتى تمكن من صنع ساعة مماثلة في البيت.

كان والده صانعا للقفازات ولكنه توفي وجاك لا يزال طفلا في السابعة فأرسلته والدته للدراسة في الدير حيث ذهب وفي حوزته صندوق معدني ملئ بالأدوات. لم يكن جاك منسجما مع باقي الأولاد ولم يكن قادرا على التركيز في دروسه فعاقبه المدير بحبسه في غرفة لمدة يومين فما كان منه إلا أن قام بروسومات استثنائية جعلت مدرس الرياضيات يقرر مساعدته.

أوتوماتونات ڤوكانسون الثلاث. لاعب الفلوت، ولاعب الطمبورين والبطة الهاضمة.

كانت عدم القدرة المالية لوالدته الأرملة هي ما دفعته للأرتباط بالدير والكنيسة والأسقف في دراسته وقد لاقت موهبته استحسانا ولكن بحدود. فبعد أن أفتتح ورشته الخاصة في مدينة ليون بدعم من أحد الأثرياء. وأثناء زيارة أحد رجال الدين للورشة أراد جاك أن يبتكر انسان آلي ليساعده في تقديم العشاء وتنظيف الطاولات ورغم أن الزائر قد بدا سعيدا بالإنسان الآلي إلا أنه سرعان ما أعلن عن إعتقاده بأن جاك له ميول وثنية وأمر بتدمير ورشته.

شعر جاك بأن ارتباطه بالكنيسة سوف يحد من قدرته على العمل في المجال الذي يعشقه فما كان منه إلا أن عاد إلى جرونوبل وأعتذر للأسقف عن عدم قدرته على القيام بالخدمة.

حين أصبح حرا، ذهب إلى باريس ويقال أنه يحضر دروسا في التشريح والطب وكان في ذات الوقت قد أعد مجموعة من الابتكارات تسمح بإقامة معرضا متنقلا. عاد جاك من جولته بعد أن ألتقى واحدا من أهم من دعموه ماديا.

وأثناء استعداده لبناء انسان آلى جديد وقع في براثن المرض وقضى 4 أشهر في الفراش. أثنلء مرضه رأى حلما بأنه صنع انسان آلي يعزف الفلوت شبيه بأحد تماثيل حديقة التويلوري فقام من الفراش ورسم تفاصيل تصميم الإنسان الآلي الجديد “عازف الفلوت” واستعان بفنانين تشكيليين وصناع ساعات حتى أكتمل الإنسان الآلي والذي كان يعزف الفلوت تماما مثل البشر وكأن التمثال قد دبت فيه الحياة.

تم عرض عازف الفلوت للمرة الأولى في عام 1738 وكانت تذكرة الدخول بثلاثة جنيهات وهو ما كان موازيا لأجر عامل لمدة أسبوع. كان جاك يعرض القطعة بنفسه لمجموعة تتكون من 10 ل 15 فرد. وحقق العرض وقتها نجاحا مذهلا فلقد كانت التفاصيل مذهله من حركة الأصابع إلى حركة الشفاه إلى كمية الهواء التي تخرج للعزف!

بعد عام واحد من عرض عازف الفلوت، عرض جاك بطة آليه بالحجم الطبيعي تحرك جناحيها وتلتقط الحبوب من ايدي رواد المعرض وتبتلعها وتهضمها وسرعان ما أصبحت تلك البطة الآلية المصنوعة من النحاس المطلي بالذهب أشهر ابتكارات فوكانسون مما دعا الكاتب والفيلسوف الفرنسي الشهيرفولتير يتهكم قائلا : لم يعد هناك شئ يذكرنا بمجد فرنسا.

في عام 1741 كان جاك قد نال كفايته من اختراعاته فطلب من بعض رجال الأعمال في ليون عرضها في انجلترا وبيعها.

كان لويس الخامس عشر شديد الإعجاب بالبطة وطلب من جاك أن يعمل مفتشا على تصنيع الحرير فلاحظ العديد من المشكلات فما كان منه إلا أن قدم مغزلا آليا يعالج جميع المشكلات التي تعاني منها فالصناعة مما أحدث ثورة في عملية تصنيع الحرير في فرنسا.

مغزل جاك الميكانيكي والذي يغني الصناعة عن العمالة البشرية آدى إلى التمرد ضده وكان العمال يرمونه بالحجارة أثناء سيره في الشارع فما كان منه إلا أن قام ببناء نول يحركه حمار ، لإثبات ، كما قال ، أن “الحصان أو الثور أو الحمار يمكنه أن يصنع قماش أكثر جمالا وأكثر كمالا من أكثرعمال الحرير قدرة.

توفى فوكانسون في باريس في سن 73 عام بعد أن بذل جهدا في جمع ابتكاراته وابتكارات غيره ليضمها لمقتنيات متحف الفنون والمهن بباريس.

ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

Jacques de Vaucanson

Jump to navigationJump to search

Jacques de Vaucanson (February 24, 1709 – November 21, 1782)[1] was a French inventor and artist who was responsible for the creation of impressive and innovative automata. He also was the first person to design an automatic loom and built the first all-metal lathe.

De Vaucanson was born in Grenoble, France in 1709 as Jacques Vaucanson (the nobiliary particle “de” was later added to his name by the Académie des Sciences[2]). The tenth child of a glove-maker, he grew up poor, and in his youth he reportedly aspired to become a clockmaker.[3] He studied under the Jesuits and later joined the Order of the Minims in Lyon. It was his intention at the time to follow a course of religious studies, but he regained his interest in mechanical devices after meeting the surgeon Claude-Nicolas Le Cat, from whom he would learn the details of anatomy. This new knowledge allowed him to develop his first mechanical devices that mimicked biological vital functions such as circulation, respiration, and digestion.[4]

Automaton inventor

At just 18 years of age, Vaucanson was given his own workshop in Lyon, and a grant from a nobleman to construct a set of machines. In that same year of 1727, there was a visit from one of the governing heads of Les Minimes. Vaucanson decided to make some androids. The automata would serve dinner and clear the tables for the visiting politicians. However one government official declared that he thought Vaucanson’s tendencies “profane”, and ordered that his workshop be destroyed.[5]

In 1737, Vaucanson built The Flute Player, a life-size figure of a shepherd that played the tabor and the pipe and had a repertoire of twelve songs. The figure’s fingers were not pliable enough to play the flute correctly, so Vaucanson had to glove the creation in skin. The following year, in early 1738, he presented his creation to the Académie des Sciences.[6]

Johann Joachim Quantz, court musician and long-time flute instructor to Frederick II of Prussia, discussed the shortcomings of Vaucanson’s mechanical flute player. In particular its inability to sufficiently move the lips resulted in the necessity of increasing the wind pressure for the upper octaves. Quantz discouraged this method as producing a shrill, unpleasant tone.[7]

At the time, mechanical creatures were somewhat a fad in Europe, but most could be classified as toys, and de Vaucanson’s creations were recognized as being revolutionary in their mechanical lifelike sophistication.

Later that year, he created two additional automata, The Tambourine Player and The Digesting Duck, which is considered his masterpiece. The duck had over 400 moving parts in each wing alone, and could flap its wings, drink water, seemingly digest grain, and seemingly defecate.[8] Although Vaucanson’s duck supposedly demonstrated digestion accurately, his duck actually contained a hidden compartment of “digested food”, so that what the duck defecated was not the same as what it ate; the duck would eat a mixture of water and seed and excrete a mixture of bread crumbs and green dye that appeared to the onlooker indistinguishable from real excrement. Although such frauds were sometimes controversial, they were common enough because such scientific demonstrations needed to entertain the wealthy and powerful to attract their patronage. Vaucanson is credited as having invented the world’s first flexible rubber tube while in the process of building the duck’s intestines. Despite the revolutionary nature of his automata, he is said to have tired quickly of his creations and sold them in 1743.

His inventions brought him to the attention of Frederick II of Prussia, who sought to bring him to his court. Vaucanson refused, however, wishing to serve his own country.[2]

Government service

In 1741 de Vaucanson was appointed by Cardinal Fleury, chief minister of Louis XV, as inspector of the manufacture of silk in France. He was charged with undertaking reforms of the silk manufacturing process. At the time, the French weaving industry had fallen behind that of England and Scotland. During this time, Vaucanson promoted wide-ranging changes for automation of the weaving process. In 1745, he created the world’s first completely automated loom,[9] drawing on the work of Basile Bouchon and Jean Falcon. Vaucanson was trying to automate the French textile industry with punch cards – a technology that, as refined by Joseph-Marie Jacquard more than a half-century later, would revolutionize weaving and, in the twentieth century, would be used to input data into computers and store information in binary form. His proposals were not well received by weavers, however, who pelted him with stones in the street[10] and many of his revolutionary ideas were largely ignored.

In 1760 he invented the first industrial metal cutting slide rest lathe.[11] The lathe was described in the Encyclopédie and is exhibited at Musée des Arts et Métiers in France. It was designed to produce precision cylindrical rollers for crushing patterns into silk cloth. [12][13] These were of copper rather than steel, so far easier to turn on a lathe, which may account for Vaucanson’s omission from such works as Derry & Williams[14], who place this invention around 1768.

In 1746, he was made a member of the Académie des Sciences.[15]

Legacy

Jacques de Vaucanson died in Paris in 1782. Vaucanson left a collection of his work as a bequest to Louis XVI. The collection would become the foundation of the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers in Paris. His original automata have all been lost. The flute player and the tambourine player were reportedly destroyed in the Revolution. Some had been sold to a glovemaker called Pierre Dumoulin (d. 1781), who exhibited them throughout Europe with great success.[16] Dumoulin’s shows with Vaucanson’s automata in Saint Petersburg started the fashion of automata in Russia.[17] In 1783, it was reported that the automata once exhibited by Dumoulin were still stored in Russia, but Dumoulin had manipulated them so that they would not work after his death.[16]

Vaucanson’s proposals for the automation of the weaving process, although ignored during his lifetime, were later perfected and implemented by Joseph Marie Jacquard, the creator of the Jacquard loom.

Lycee Vaucanson in Grenoble is named in his honor, and trains students for careers in engineering and technical fields.

See also

References

- ^ Jacques de Vaucanson at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Jump up to:a b Account by Christiane Lagarrigue[unreliable source?]

- ^ Mahistre, Didier. “Jacques de Vaucanson”. Archived from the original on 2004-06-12. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ^ “Jacques de Vaucanson (1709-1782)”. Archived from the original on 2004-03-06. Retrieved 2004-01-17.

- ^ Wood, Gabby. “Living Dolls: A Magical History Of The Quest For Mechanical Life”, The Guardian, 2002-02-16.

- ^ “Essay by Peter Schmidt, Swarthmore College”. Archived from the original on 2017-07-02. Retrieved 2004-01-15.

- ^ Quantz, Johann Joachim (1752). Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen [Attempt at instruction in playing the transverse flute] (in German). Berlin, (Germany): Johann Friedrich Voß. p. 46. Available at: Deutsches Text Archiv

- ^ “Vaucanson’s Mechanical Duck”. Archived from the original on 2017-07-02. Retrieved 2004-01-15.

- ^ Chronology of Lyon

- ^ Gaby Wood (2002). Edison’s Eve. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

- ^ David M. Fryer, John C. Marshall (April 1979). “The Motives of Jaques de Vaucanson”. Technology and Culture. 20 (2): 257–269. doi:10.2307/3103866. JSTOR 3103866.

- ^ https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/metal-turning-lathe/kwGbpYqKSyzcSg

- ^ https://www.arts-et-metiers.net/musee/tour-charioter-de-vaucanson

- ^ T.K. Derry & Trevor I. Williams (1960). A Short History of Technology.

- ^ Biography at Vaucanson.org (fr) Archived 2003-12-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wang, Yanyu (2020). “Jacques de Vaucanson (1709-1782)”. In Ceccarelli, Marco; Fang, Yibing (eds.). Distinguished Figures in Mechanism and Machine Science: Their Contributions and Legacies, Part 4. New York: Springer. pp. 15–46.

- ^ Collis, Robert (2005). ““A Veritable Eldorado”: European Wondermongers in Russia, 1755-1803″. In Waegemans, Emmanuel; von Koningsbrugge, Hans; Levitt, Marcus; Ljustrov, Mikhail (eds.). A Century Mad and Wise: Russia in the Age of the Enlightenment. Groningen: INOS Intitute for Northern and Eastern European Studies. pp. 489–517. ISBN 978-9081956888.